Sometimes deaths come in spates. In 2016 we lost several famous rock stars, including David Bowie, Prince, Leonard Cohen and George Michael. I hope 2019 isn’t turning into the year that we lose too many rock stars of the future/visionary world. In 2019 Bernard Lietaer passed away, and last week I heard that Barbara Marx Hubbard had died. She was 89 years old, admittedly, but had been in excellent health until a swollen knee led to a chain of events that ended with her life support being turned off.

I never met Barbara, as I never met Bernard, and yet both had a significant influence on my worldview, particularly on how I perceive the future and what needs to happen to make it both peaceful and sustainable. As you have hopefully gathered from recent blog posts, I am extremely doubtful that we can solve our problems from within the same structures that have created them, and believe that we need a new narrative about what it means to be human in the 21st century: as Alex Evans puts it in The Myth Gap, we need a narrative that embodies “a larger us, a longer now, a better good life”.

I never met Barbara, as I never met Bernard, and yet both had a significant influence on my worldview, particularly on how I perceive the future and what needs to happen to make it both peaceful and sustainable. As you have hopefully gathered from recent blog posts, I am extremely doubtful that we can solve our problems from within the same structures that have created them, and believe that we need a new narrative about what it means to be human in the 21st century: as Alex Evans puts it in The Myth Gap, we need a narrative that embodies “a larger us, a longer now, a better good life”.

If you’re not familiar with Barbara’s work, I will attempt to do it some small amount of justice in this blog post, and I’d also encourage you to watch one of her talks, like this one. Her central thesis was that, after millions of years of evolution on Planet Earth, we are the first species to be aware of the process of evolution, so it is incumbent on us to use that awareness to consciously manage our future evolution.

She has sometimes been disparagingly referred to as part of the New Age movement, but I think this is to do her a disservice. She brought immense intellectual curiosity to her work, with great questions being her particular stock in trade.

A turning point in Hubbard’s life was the end of World War II and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. “What was all this power for?” she wondered.

In 1952, her father took her to see President Eisenhower in the Oval Office. “What can I do for you, young lady?” he asked casually. “Mr. President,” she said, “I have a question for you. What is the meaning of our new powers that is good?”

He looked startled, shook his head, and said, “I have no idea.”

Then we better find out, she thought, and the quest for a vision of the future equal to our new power became the driving question of her life.

This question also led her to meet her husband. She was a student at Bryn Mawr in Pennsylvania when she took a year out in Paris. One day, while hanging out in a Parisian café, she struck up a conversation with an artist, a man by the name of Earl Hubbard. She asked him the questions she had been asking everyone, the questions inspired by Hiroshima: “What do you think is the meaning of our new power that is good, and what do you think is your purpose?” This young man had an immediate answer: “I’m seeking a new image of man commensurate with our power to shape the future. When a culture loses its story, loses its self-image, it loses its greatness. The artist has to find a new story and until it is expressed by artists, we won’t be able to bring our culture to fruition.” Her only response was a small voice in her mind that said, “I’m going to marry him.”

And she did. And went on to have five children as a housewife in Connecticut. But she needed more than domestic bliss, and started reading books in search of answers.

It started with Maslow’s Toward a Psychology of Being. He said that every self-actualizing person has one thing in common: a chosen vocation they found intrinsically self-rewarding. Here she found a great clue to conscious evolution: the need to find innate life purpose that transcends mere selfish desire to prevail, with vocation being a vital way of directly experiencing the evolutionary impulse.

Then came Teilhard de Chardin. She wrote later: “This was the real opening. I could tell from his Law of Complexity/Consciousness — the understanding of God in evolution rising to higher consciousness, freedom and more complex order, that my own impulse to grow, to be more, to realize my potential was not the musings of a neurotic housewife, but rather, it was the universe unfolding in me as me.”

Then came Buckminster Fuller, who told us that we have the resources, technologies and know-how to make of humanity a 100% physical success without destroying our environment.

It was February 1966 when she had a life-changing vision while walking on a frosty hill near her Connecticut home. She wrote:

“I asked the universe a question: “What is Our Story? What on Earth is comparable to the birth of Christ?” What I meant by that is the Gospels were such an amazingly effective story. What could be our story comparable in power to that?

Suddenly, my mind’s eye penetrated the blue cocoon of earth and lifted me up into the utter blackness of outer space. A Technicolor movie turned on. I felt the earth as a living organism, heaving for breath, struggling to coordinate itself as one body. It was alive! I became a cell in that body.

In the next few minutes I saw conscious evolution as the next stage of evolution itself. It is the evolution of evolution from unconscious to conscious choice. I realized that we are literally in a crisis of birth of the next stage of our evolution. We are outgrowing the womb of self-conscious humanity and planet-boundedness. We can learn to restore the Earth, free ourselves from scarcity and move forward into an immeasurable future as a co-evolutionary co-creative species. Like a newborn infant, we innately know how to do this…. when we have the right story to guide us.”

She dedicated herself to learning the story and to telling it in every way that she could. She believed that Maslow was right, in that a true vocation is a key to participation in conscious evolution.

“I see vocation as the enfolded implicate order, the process of creation localizing and unfolding in each of us as our own passion to create. Once that happens the Consciousness Force internalizes and we enter the process of conscious self-evolution. We become conscious evolutionaries.”

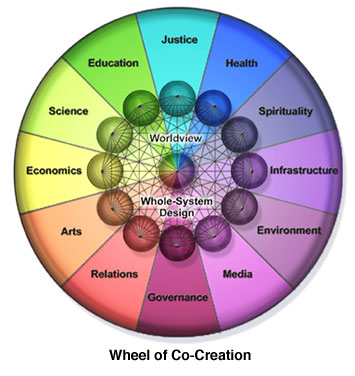

She saw the essential task of conscious evolution as being “to learn how to be responsible for the ethical guidance of our evolution. It is a quest to understand the processes of developmental change, to identify inherent values for the purpose of learning how to cooperate with these processes toward chosen and positive futures, both near term and long range.”

She boiled this down to “the three C’s:”—new cosmology, new crises, and new capacities.

Our new cosmology is the story that science has revealed about where our universe came from, about the extraordinary process of which we are a part. It is important, Hubbard wrote, because it gives us “a new sense of identity, not as isolated individuals in a meaningless universe but rather as the universe in person” Our new crises, she explained, are those potentially catastrophic global issues we face, such as climate change. In light of evolution’s trajectory, these are reframed as a “natural but dangerous stage in the birth process” of our next evolutionary stage. Hubbard points out that there have always been crises as part of the process—mass extinctions, ice ages, and so on—but never before have we had advance warning of our pending self-destruction and therefore had the opportunity to do something about it. We are shifting, she wrote, from “reactive response to proactive choice.”

The third piece in Hubbard’s triad, new capacities, are recently developed powers such as biotechnology, nuclear power, nanotechnology, cybernetics, artificial intelligence, and artificial life. She acknowledged that in our current state of “self-centred consciousness” these are potentially hazardous, and yet, she suggests, they may be exactly what we need for the next phase of our evolution. She cautioned against acting out of fear and prematurely destroying these new technologies. The task of conscious evolution is rather to “guide their capacities toward the emancipation of our evolutionary potential.”

She saw a special role for women in the emerging new consciousness: “An evolutionary woman is activated by an inner impulse to create, to love more, be more, create more and give more… The evolutionary woman is able to love what’s being born in her – the creative feminine – and able to love giving her gift to the unknown world.”

I will give the last word to BMH:

“Perhaps we are indeed coming to the end of this world, to the end of civilization, the end of separate self consciousness as we have known it. And this is good. We are being instructed by Failure – the failure of war to win, the failure of consumerism to satisfy, the inevitable rise of the seas in response to global warming brought on in part at least by human destruction of nature. All of these evolutionary drivers may indeed be the impulse needed to jump our species to a higher order, or to self destruction.”

She lived a long and prolific life, and many will miss her, but she has left a huge legacy of thought leadership, books, and presentations. Although I don’t particularly believe in a heaven as such, I nonetheless like to imagine that her spirit is now somewhere where she can ask great questions to her heart’s content, and get the answers she so enthusiastically sought.