Well, well, it has been an interesting week since I published my blog post about capitalism and what’s wrong with it.

First of all, let me say how grateful I am for having such a wide range of readers. When we hear in the media about the problem of isolated echo chambers and news bubbles… well, this blog’s audience is clearly both wider and wiser than that. And I celebrate you.

Secondly, I sincerely thank all those who took the trouble to write. You have definitely contributed to my knowledge and broadened my perspectives. You have also demonstrated something that we don’t see often enough in political circles, or at least in the US and the UK we don’t – a civilised exchange of views, in which we may agree to disagree, but at least both sides have listened, and responded rather than merely reacted. I appreciate it.

Thirdly, I notice how the emails of approval tended to be short (“Awesome thread of thought and well needed!” “a breath of fresh air in this pro capitalist nightmare” “wonderful work”), while the dissenting emails tended to be much longer, and in some cases conveyed desperate concern, as if I am a wayward child in danger of losing my immortal soul to the perils of communism. The word “Marxist” has come up more than once.

Fear not, dear reader. Just because I am not a fan of neoliberal capitalism does not mean I am a Marxist, socialist, communist, nor Corbynista.

Maybe this is part of the problem with our current thinking – the dualism that dictates that if we say we’re not one thing, the assumption is that we are its perceived “opposite”, while there is actually a whole spectrum of options.

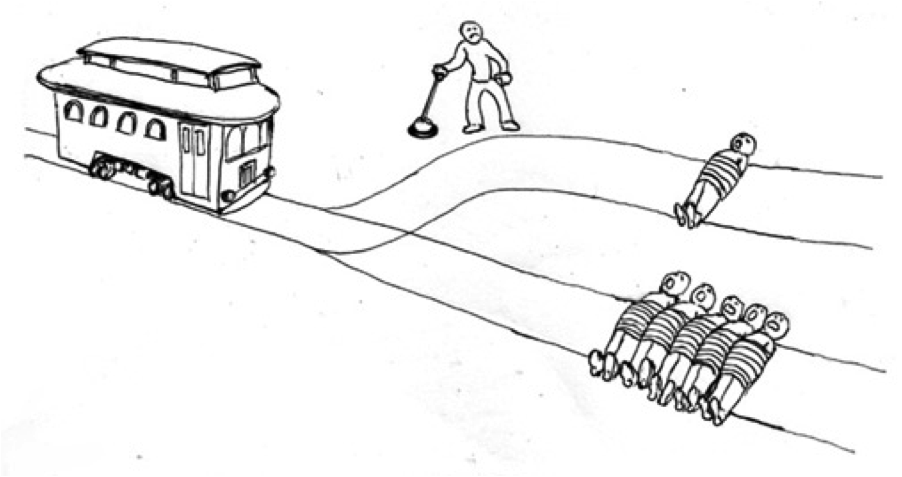

If I were to apply any label to myself (and I’m not a big fan of labels, finding them over-simplistic), I would opt for “utilitarian”, with utilitarianism being defined as something like: “an ethical theory that determines right from wrong by focusing on outcomes. It is a form of consequentialism. Utilitarianism holds that the most ethical choice is the one that will produce the greatest good for the greatest number”. To that I would add “over the longest period of time, and relating to non-human as well as human actors”.

I am not going to be an apologist for Jason Hickel – he can do that for himself, as in this open letter disputing Steven Pinker’s much more rosy view of the current era. I don’t particularly appreciate Hickel’s tone – he adopts the condescension and faux politeness so often deployed in public arguments – but he makes some valid points to rebut Pinker’s critique. I’d specifically like to highlight this passage:

“Let me be clear: this is not a critique of industrialization as such. It is a critique of how industrialization was carried out during the period in question. If people had willingly opted into the capitalist labour system, while retaining rights to their commons and while gaining a fair share of the yields they produced, we would have a very different story on our hands. So let’s celebrate what industrialization has achieved – absolutely – but place it in proper context: colonization, violence, dispossession and all.”

Capitalism is not bad in itself – the fault lies in the way that it has too often been deployed (see Theory of Flaws).

Hickel’s main point is:

“What matters… is the extent of global poverty vis-à-vis our capacity to end it. As I have pointed out before, our capacity to end poverty (e.g., the cost of ending poverty as a proportion of the income of the non-poor) has increased many times faster than the proportional poverty rate has decreased.”

So yes, as a percentage, poverty is decreasing – but nowhere near as much as it could have done if we were genuinely trying to deliver the greatest good to the greatest number.

This led me to wondering: is the greatest good served by increasing income?

It might sound obvious that it would be, but I’ve been to villages where people have no electricity, extremely limited infrastructure, and a diet consisting of a narrow range of locally available foods – yet as night fell the forest would echo to the sound of laughter, rarely heard in the developed urban world. Was this just an anomaly, or could we be wrong in assuming a direct causal relationship between money and happiness?

Overall, the evidence shows that yes, richer people are happier (lots of great data here). You may have heard of the Easterlin paradox where, in the US and Japan, reported levels of happiness appeared to stagnate despite an increase in average GDP per capita. However, according to this article, it appears that in Japan this was due to changes in the questions being asked about subjective happiness, so they weren’t comparing like with like, and in the US the plateau in wellbeing was due to the inequality of distribution – the increase in wealth was confined to the top few percent. At an individual level, there are of course happy poor people and miserable rich people, but in general it’s a lot easier to be happy if you have access to decent food, clean water, shelter, and healthcare.

Overall, the evidence shows that yes, richer people are happier (lots of great data here). You may have heard of the Easterlin paradox where, in the US and Japan, reported levels of happiness appeared to stagnate despite an increase in average GDP per capita. However, according to this article, it appears that in Japan this was due to changes in the questions being asked about subjective happiness, so they weren’t comparing like with like, and in the US the plateau in wellbeing was due to the inequality of distribution – the increase in wealth was confined to the top few percent. At an individual level, there are of course happy poor people and miserable rich people, but in general it’s a lot easier to be happy if you have access to decent food, clean water, shelter, and healthcare.

If you check out Dollar Street – which I strongly encourage you to do – you can see for yourself how the rest of the world lives. The team visited 264 families in 50 countries and collected 30,000 photos, then arranged them by level of income. So on the site you can zoom in on a family in Burundi living on $27 a month, and see their land, toys, stove, plates, water supply, cleaning materials, food, front door, bathroom facilities, shoes, teeth, beds, and so on. And a family living in the US on $4,446 a month. (Sadly it seems Jeff Bezos was not available to have his bathroom facilities photographed.) And many other countries and income levels besides.

One thing we notice from these photographs is that poor people generally have a lot less stuff than rich people. They have smaller houses, eat less, buy less, travel less, and have a lesser environmental impact (although are often in the front line of environmental disasters).

Yes, we want to end poverty – which, by implication, means we want poor people to have access to more food, more comfort, more of the good things in life. And here we run, yet again, into the inescapable logic of the IPAT equation:

Impact = Population x Affluence x Technology.

If the Affluence of developing countries is going to increase, and it’s unlikely that Technology can improve efficiency enough to counterbalance it, then if we want to hold Impact constant (or better still, reduce it) either we need to reduce Population, and/or we need to distribute Affluence more effectively in order to deliver the greatest good to the greatest number.

Oh wow, if capitalism was a controversial issue, now I’m really going in deep with population and wealth redistribution… Ah well, in for a penny, in for a pound. Let’s have this conversation! (to be continued)

P.S. I can’t not mention this. The other morning I was listening to BBC Radio 4, and after all the usual headlines about Brexit, Boris, etc. etc., the final headline was that insects are in catastrophic decline and could all but disappear by the end of the century, leading to the collapse of nature, which would be shortly followed by the extinction of humanity.

P.S. I can’t not mention this. The other morning I was listening to BBC Radio 4, and after all the usual headlines about Brexit, Boris, etc. etc., the final headline was that insects are in catastrophic decline and could all but disappear by the end of the century, leading to the collapse of nature, which would be shortly followed by the extinction of humanity.

Really?? The possible extinction of humanity within a century – the last headline??!

Or maybe I’ve just got my priorities all wrong. Clearly the imminent fiasco that is Brexit, or Boris Johnson’s latest utterances, are a lot more important than human extinction.

P.P.S. I’d be interested to hear your views on David Malpass, Trump’s nominee to head up the World Bank. I found his article in the FT, What I would do as the Next President of the World Bank, rather colonialist and patronising towards poorer countries, while also perpetuating the myth of the possibility of infinite growth on a finite planet. Oh, and until now I hadn’t realised that the president of the World Bank is ALWAYS an American, and in the couple of cases where the nominee is not, they are naturalised as US citizens first.

P.P.S. I’d be interested to hear your views on David Malpass, Trump’s nominee to head up the World Bank. I found his article in the FT, What I would do as the Next President of the World Bank, rather colonialist and patronising towards poorer countries, while also perpetuating the myth of the possibility of infinite growth on a finite planet. Oh, and until now I hadn’t realised that the president of the World Bank is ALWAYS an American, and in the couple of cases where the nominee is not, they are naturalised as US citizens first.

Might it not make more sense to have the bank headed up by someone who really, deeply understands the problems they are trying to alleviate? Maybe just occasionally?