The bluefin tuna is an amazing fish. According to the WWF website:

“Bluefin are the largest tuna and can live up to 40 years. They migrate across oceans and can dive more than 4,000 feet. Bluefin tuna are made for speed: built like torpedoes, have retractable fins and their eyes are set flush to their body. They are tremendous predators from the moment they hatch, seeking out schools of fish like herring, mackerel and even eels. They hunt by sight and have the sharpest vision of any bony fish.”

Unfortunately for bluefin tuna, they are also delicious. In 2013 it was reported that they had suffered a catastrophic decline in stocks in the Northern Pacific Ocean, of more than 96%. Even worse, most of the tuna being fished were juveniles that had not yet reproduced, threatening the future of the species.

Unfortunately for bluefin tuna, they are also delicious. In 2013 it was reported that they had suffered a catastrophic decline in stocks in the Northern Pacific Ocean, of more than 96%. Even worse, most of the tuna being fished were juveniles that had not yet reproduced, threatening the future of the species.

Money is playing a key role in the demise of the bluefin tuna. Mitsubishi, the car and electronics company, is not only investing heavily in tuna, they are stockpiling it in freezers in order to drive up the price. The rarer it gets, the more valuable it becomes. Once all the wild bluefins have gone, Mitsubishi’s frozen assets will be gradually released to the market at peak price.

Financially, there is every incentive to render the bluefin tuna extinct. Ethically, we have to question a system of incentives that produces such a result.

Yes, I know that over the last couple of hundred years capitalism has led to massive leaps forward in human wellbeing. Healthy competition has encouraged creativity and innovation. Rising wages have enabled huge rises in the standard of living. Philanthropy has improved the lot of many.

But I believe we need a new form of economics that will remedy the failings of capitalism as it is currently practiced. Many books have been written on this subject, so in this blog post I can only skim the surface of a much bigger topic, but here are a few reasons, right off the top of my head, why we need to take a long hard look at the monopoly of capitalism.

- Externalisation of costs

If the goal of capitalism is maximisation of profit, then the incentive is to minimise costs. So if your company can exploit natural resources for next to free, then it will. As John Paul Getty said, “Formula for success: rise early, work hard, strike oil.” If the pure capitalist shows any restraint in the extraction of oil, precious metals, etc, it is not out of regard for the future, but to avoid flooding the market and hence reducing the price.

Likewise, if the capitalist can save the cost of disposing of unwanted by-products by dumping them into the air or a nearby river, he/she will do so, regardless of the consequences for humans and wildlife. Capitalism has no mechanism for discouraging exploitation or pollution, as they have no monetary cost, unless poor PR leads to reduced demand for the company’s goods. The blatant disregard of many companies for the environment has led to calls for the criminalisation of their degradation of our earth, air, and water – see Polly Higgins’ Ecocide campaign.

Civil society may organise protests to express their disgust at the environmental destruction, but companies will rarely respond until compelled to do so by government, which leads us to….

- Corporate lobbying

(See earlier blog post on democracy.) Powerful industry lobbies can, and do, influence government through some strategically placed funding. They can also invest in…

- Bad science

Nicotine isn’t addictive. Climate change doesn’t exist. Pesticides and herbicides do no harm (despite being poisons).

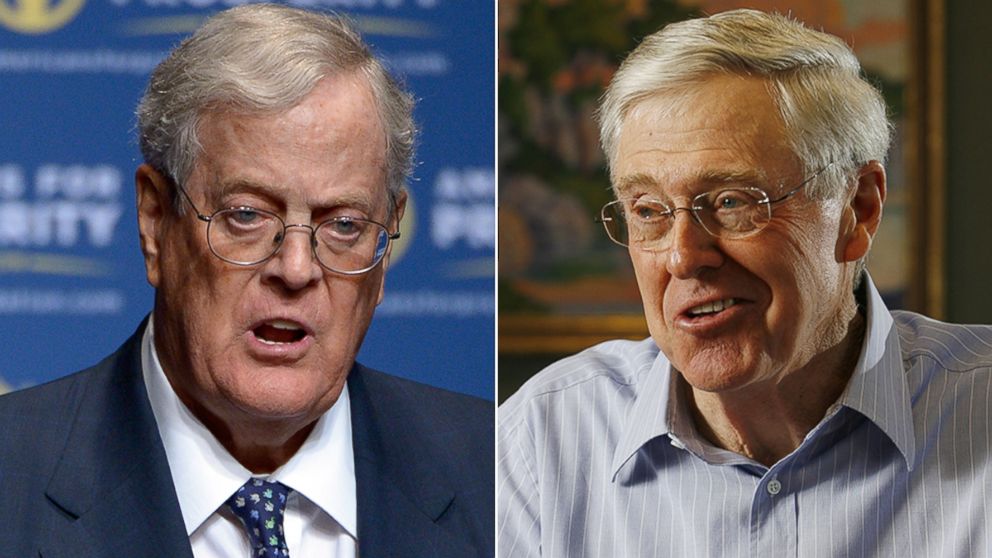

If you haven’t yet seen “Merchants of Doubt”, please do, or at least watch the trailer. It shows how there has been a concerted campaign of misinformation. Conservative think tanks with warm-and-cuddly-sounding names like Americans for Prosperity, Freedom Partners, Heritage Foundation, the Institute for Humane Studies, are funded by the rich and powerful to cast doubt on sound science and sow seeds of confusion in the collective public mind. (Oh, and those are just the think tanks funded by the Koch Brothers, described by The New Yorker as “longtime libertarians who believe in drastically lower personal and corporate taxes, minimal social services for the needy, and much less oversight of industry—especially environmental regulation.” There are many, many more such organisations.) If you ever see reports of a “study” claiming that something is safe – check who funded it, and then who funded them. Follow the money.

- The mono-metric

“Perhaps what you measure is what you get. More likely, what you measure is all you’ll get. What you don’t (or can’t) measure is lost” – H. Thomas Johnson

So if all you measure is money – which is tempting, as money is so nice and easy to measure – then it’s unlikely that you will place much value on environmental stewardship, staff engagement, health, and wellbeing, unless and until they start to impact on your bottom line. Caring about staff wellbeing because sick days are impacting your profitability, or caring about the environment because ethical consumers are boycotting your products – that’s not really caring. That’s money.

You may tell me that we have BCorps and other companies that embrace the triple bottom line of people, planet, profit – and yes, this is true. But John Elkington, the man who coined the phrase “triple bottom line” recently issued a product recall on his concept, saying:

“Fundamentally, we have a hard-wired cultural problem in business, finance and markets. Whereas CEOs, CFOs, and other corporate leaders move heaven and earth to ensure that they hit their profit targets, the same is very rarely true of their people and planet targets. Clearly, the Triple Bottom Line has failed to bury the single bottom line paradigm. Critically, too, TBL’s stated goal from the outset was system change — pushing toward the transformation of capitalism. It was never supposed to be just an accounting system. It was originally intended as a genetic code, a triple helix of change for tomorrow’s capitalism, with a focus was on breakthrough change, disruption, asymmetric growth (with unsustainable sectors actively sidelined), and the scaling of next-generation market solutions.”

He goes on to point to companies that are genuinely embracing TBL as it was intended, but it is a short list. Profit still has a virtual monopoly as a corporate success metric.

- Short term thinking

As I’ve said recently, I regard myself as essentially a utilitarian, curious about how we create systems that deliver the greatest good to the greatest number over the longest period of time. But this runs counter to short-term corporate reporting, and pressure to deliver maximum returns to shareholders. It’s encouraging to see organisations like Ceres working to “advance sustainability leadership among investors, companies and capital market influencers to drive solutions and take stronger action on the world’s biggest sustainability challenges, including climate change, water scarcity and pollution, and human rights abuses.” But there is still a long way to go. Extractive industries such as fossil fuels and minerals cannot, by definition, be sustained indefinitely. Industries such as fishing and farming have the potential to be sustainable, but are mostly not – current practices are leading to population crashes of many fish species, and to catastrophic degradation of the soil.

In too many ways, we are killing the goose that lays the golden egg of our future food supply.

So, what to do about all this?

Despite what some readers may think, I am not anti-capitalist, but I do believe that it is dangerous to have a neoliberal monoculture. Capitalism is well suited to some industries (technology, cars, electronics) but not to others (healthcare, nature conservation, social services).

To have a more resilient economy, and a more sustainable lifestyle, we need to embrace an ecosystem of types of currency that operate in different ways to motivate different kinds of behaviour. As Bernard Lietaer said:

To have a more resilient economy, and a more sustainable lifestyle, we need to embrace an ecosystem of types of currency that operate in different ways to motivate different kinds of behaviour. As Bernard Lietaer said:

“A complementary currency is a medium of exchange other than conventional money… I am talking about using this proven technology, characteristic of the information age, and using it to do things that do make a difference, by changing behaviour towards the environment and other people, encouraging people to do things that they wouldn’t do spontaneously… The alternative to using currency for this function is to create laws requiring or forcing people to do such things. With a currency you create a pull rather than a push, and that is a lot more attractive. You choose your objectives and specifically design your currency to achieve them.”

So, in my view, this is the way forwards – a multiplicity of currencies, some geographically based (such as the Brixton/Bristol/Totnes Pounds), some functionally based (Dashboard.Earth, Eco Coin, Women’s Coin, etc.) and so on, to create an interconnected web of financial-ish incentives to get more of the behaviours that will lead us towards a peaceful and sustainable future.