Forgive me, dear reader, for I have not blogged for eight months, since I finished teaching my courage class at Yale. But I have not been idle. There has been much going on behind the scenes, which I will gradually share with you.

To get started, I wanted to create a list of the books that most impacted my thinking in 2017, and share the ideas that I took away from them. This blog post ended up being considerably longer than intended, but if you’re interested in psychology, neuroscience, and the nature of reality, I trust you will find it interesting.

Deviate: The Science of Seeing Differently, by Beau Lotto

I had to miss Beau Lotto’s talk in London for the How To Academy (great speaker events) due to a diary clash, but I did get the book. He also has a TED Talk, but the book is better and deeper.

I had to miss Beau Lotto’s talk in London for the How To Academy (great speaker events) due to a diary clash, but I did get the book. He also has a TED Talk, but the book is better and deeper.

His main thesis is that the brain didn’t evolve to see accurately, but rather, usefully. It was the genes that were best able to assess threats and problems that survived. The genes for accuracy were less valuable than the genes for avoiding large mammals with big teeth.

So what does this mean? We can all tell what’s real and what’s not, right?

Wrong.

There are various reasons why our ability to perceive reality is limited:

- We don’t sense all there is to sense. Other creatures have access to far more sensory information than we do. E.g. Birds can detect polarization of light. Stomatopods have 16 visual pigments compared with our 3. Bats can echolocate. Polar bears can smell a seal from 20 miles away, or 3 feet under the ice. Human senses are very poor and weak by comparison.

- The information we take in is in constant flux. Everything changes and moves, so by the time we have processed the sensory information, it is already out of date.

- All stimuli are highly ambiguous. Many perceptions are the end result of a multiplicity of factors, e.g. Visual perception is affected by clarity of air, perspective, etc. The eye is also often distracted by movement, at the expense of static objects.

- There is no instruction manual. Perception evolved to guide us in how we react. But the perception doesn’t tell us how to react – we supply that part. The brain creates a meaning that generates the response.

And I would add 5. Our vision is affected by our scale. A tadpole will perceive things very differently than a blue whale, because what presents an existential risk to a tadpole (i.e. is big enough to eat it) does not present a risk to a whale (because there is nothing big enough to eat it – at least not in one gulp).

Following on with this them of reality not being as real as we think it is…

Liminal Thinking: Create the Change You Want by Changing the Way You Think, by Dave Gray

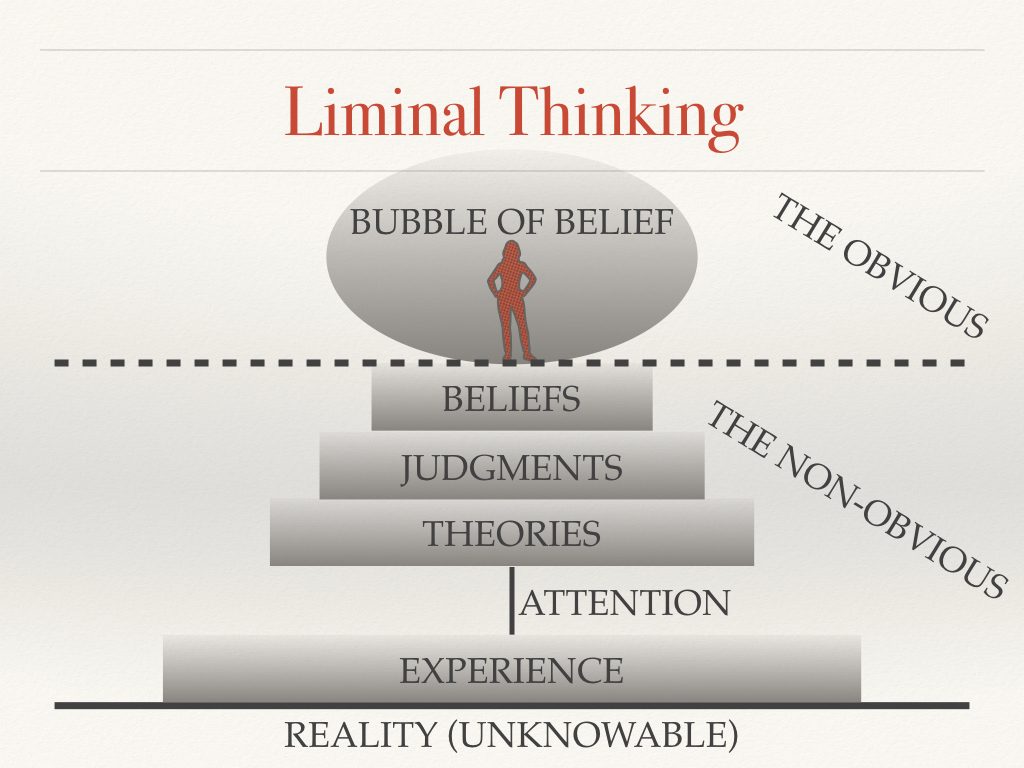

Follows on well from Deviate. Again, the idea is that our brain sits blindly in the black box of our skull, receiving information from our sensory peripherals – eyes, ears, nose, tongue, nerve endings – and doing its best to create a map that is useful in helping us navigate the world, and may incidentally also bear some resemblance to reality – but that is by no means essential.

From the moment we’re born, our experiences start to shape our view of reality. For example, if we’re unfortunate enough to be badly parented, we may be hyper-alert for facial expressions indicating anger, to the extent that we perceive anger where there is none, because a false positive is more useful to us than failing to notice the danger signs when anger is looming.

Human attention is a rather poor and feeble thing – (according to Dr Bruce Lipton, in The Biology of Belief) our conscious mind can process 40 bits of information per second, compared with the stunning 20 million bits of information per second that our subconscious can handle. So we have to be very selective where we place our narrow beam of conscious attention. Naturally, it picks out the bits of information that have proved to be most useful to it in the past, based on our experiences.

Then, based on our experiences and hence our attention, we form theories, judgments and beliefs about the world around us, in order to efficiently assess and predict our “reality”. The brain uses a lot of energy, so it loves shortcuts, and the more preconceptions we have about reality, the less work the brain has to do. As William James said, “A great many people think they are thinking when they are merely rearranging their prejudices”. Or, as Anaïs Nin observed, “We see the world not as it is, but as we are.”

So, we sit atop this tottering edifice of assumptions and prejudices inside our bubble of belief, and think it is reality. So convinced are we that the contents of our bubble are real, that when we encounter someone who inhabits a different kind of a bubble, we think they must be ignorant, stupid, or evil, simply because they see the same “reality” a different way than we do.

And this bubble can be very difficult to penetrate. The problem is that there is a two-step process for accepting new information:

- Is this new data consistent with what I already “know” about the world?

- If this data does happen to be true, does the world make more sense?

Unfortunately we usually don’t get to Step 2 if the new data doesn’t pass Step 1. The brain loves coherence, preferring it to accuracy, so if the new data is not consistent with our existing mental models, it normally gets rejected outright – as any climate change campaigner who has argued with a climate change denier will know. All too often, the more fragile someone’s confidence in their existing worldview, the more staunchly they will defend it. An attack on their beliefs becomes an attack on their very identity.

(I’m sure we can all think of someone we know who seems to inhabit a very odd bubble of belief. But remember you are in one too, and yours seems as odd to them as theirs does to you.)

The best way to sneak under the radar here is to use not data and graphs, which give the brain advance warning that hostile data may be incoming, and will likely set the mental sirens blaring on red alert, but rather to use stories as a Trojan Horse for new information.

Bringing me nicely to….

Retellable: How Your Essential Stories Unlock Power and Purpose, by Jay Golden

(available as a free download here)

(available as a free download here)

Jay does a great job of showing how to tell great stories with a compelling arc that will have your audience eagerly hanging on your every word. Humans love stories, and being a superb raconteur is definitely a learnable skill. (If you have the knack, humour goes a long way too – compare this flight attendant’s safety briefing with the usual tedious gubbins, and decide which you’re more likely to pay attention to.)

(Jay happens to be the brother of Dane Golden, my old friend from the days of the Roz Rows the Pacific podcast with Leo Laporte. So I got in touch and we had a looooong conversation about the pleasures and power of narratives.)

So what would it look like if we created a compelling new narrative to fill…

The Myth Gap: What Happens When Evidence and Arguments Aren’t Enough, by Alex Evans

I bought this book after hearing Alex Evans talking one morning on BBC Radio 4 about the need for new myths to replace the outdated religious and folk stories, if we are to create a better vision for the future. Amen to that, I thought, and I looked him up on the internet and emailed him to say how much I appreciated his ideas. I’ve since met Alex, who just happens to live close to my mum.

I bought this book after hearing Alex Evans talking one morning on BBC Radio 4 about the need for new myths to replace the outdated religious and folk stories, if we are to create a better vision for the future. Amen to that, I thought, and I looked him up on the internet and emailed him to say how much I appreciated his ideas. I’ve since met Alex, who just happens to live close to my mum.

His criteria for a good myth is that it unites rather than divides (wouldn’t that be nice?), and that it calls forth from people the kind of behaviours that contribute positively to society: purpose, health, prosperity, peace.

Specifically – and he is really talking my language here – a good myth should promote the concepts of:

- a larger us (moving beyond the individualistic and even the national, to recognise that we are all humans, living together on a shared planet)

- a longer now (see the ideas of the Long Now Foundation, founded by Danny Hillis, who I also met in 2017)

- a different good life (where success is defined not what we consume, but by who we are)

Ever since I read this report by the WWF and ZSL, with its diagram of a systems approach to change, I’ve been fascinated by the idea of underlying narratives/mental models, and how they need to change if we are to achieve genuine and all-pervading sustainability, rather than dealing with problems piecemeal. What got us through the last 10,000 years won’t get us through the next. We need a new story about what it means to be a human being in the 21st century.

A new narrative to underpin a major shift in consciousness – how hard can it be?!

It can be very hard, because these narratives form the absolute foundations of our modern society, according to…

Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, and Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow, by Yuval Noah Harari

According to Harari’s interpretation, the main reason that human beings have thrived as a species is that we are (as far as we know) uniquely capable of responding effectively and flexibly to a changing world. The main characteristic that enables this effective and flexible response is our ability to collectively create and believe in shared fictions, like money, countries, governments, legal systems, and corporations. None of these things have an objective existence outside of the human mind, but we believe in them as if they are real, and on these beliefs our entire modern enterprise is founded. Harari takes a hard look at many of these shared stories, and suggests the perils that lie ahead.

According to Harari’s interpretation, the main reason that human beings have thrived as a species is that we are (as far as we know) uniquely capable of responding effectively and flexibly to a changing world. The main characteristic that enables this effective and flexible response is our ability to collectively create and believe in shared fictions, like money, countries, governments, legal systems, and corporations. None of these things have an objective existence outside of the human mind, but we believe in them as if they are real, and on these beliefs our entire modern enterprise is founded. Harari takes a hard look at many of these shared stories, and suggests the perils that lie ahead.

The good news, in my view, is that if these fictions become no longer fit for purpose, we can change them, because we created them in the first place. The not so good news is that we seem to have forgotten that these are human-made fictions, and treat them as if they are objectively real.

It can take real courage to step outside of these collective fictions, like this guy did….

Moneyless Man: A Year of Freeconomic Living, by Mark Boyle

Moneyless Man: A Year of Freeconomic Living, by Mark Boyle

Mark Boyle decided to opt out of one of these shared fictions – the financial system – by spending a year living entirely without money. The practical challenges were considerable, but he also found great joy in the simplicity of his life, better health, and a sense of community with other people also seeking to live simpler lives with a lighter footprint. You could even say that, without the option to throw money at a problem, he was more connected to reality – the reality of where food, fuel and electricity come from, the reality of needing to share resources for survival, and the reality of true sources of happiness and wellbeing.

Which creates a nice segue to….

Happier People, Healthier Planet, by Teresa Belton

The author put an advert in The Big Issue (newspaper sold by homeless people to earn money) to invite responses from people who had made a conscious choice to live more frugally. Her research found that low impact living generally leads to impressively high levels of self-reported life satisfaction. This is a well researched and fascinating book that looks at low impact living from many social, economic, and psychological perspectives.

The author put an advert in The Big Issue (newspaper sold by homeless people to earn money) to invite responses from people who had made a conscious choice to live more frugally. Her research found that low impact living generally leads to impressively high levels of self-reported life satisfaction. This is a well researched and fascinating book that looks at low impact living from many social, economic, and psychological perspectives.

In keeping with my general theme of the year, the book also touches on the nature of reality. Psychologist Nick Baylis “identified three cognitive-behavioural processes in which most people partake to some degree; he terms these ‘quick fixes’, ‘reality evasion’ and ‘reality investing’. Quick fixes are strategies such as eating or drinking too much, gambling and retail therapy, while reality evasion involves denial of circumstances, escapism through excessive television watching or computer games playing, or hard drugs. Reality investment, by contrast, involves planning, practising of skills, pursuit of learning and the cultivation of good health. According to Baylis, reality investment is the defining characteristic of a positive relationship with reality; and reality investment is likely to enhance well-being. It is also, surely, the only form of relationship with reality that can further the cause of environmental sustainability. This is because studies have shown that happy people are not starry-eyed; those who have a positive outlook on life actually have a better grip on reality than the unhappy. They are better at attending to relevant information, including the negative and threatening, and are more realistic about what they can and cannot achieve. They have also been found to have greater self-control and self-regulatory abilities, and tend to be more co-operative, pro-social, charitable and ‘other-centred’. These are all qualities which are likely to incline individuals to consider the ethical dimensions of their consumption decisions.”

And speaking of happiness…

The Happiness Hack: How to Take Charge of Your Brain and Program More Happiness Into Your Life, by Ellen Petry Leanse

The Happiness Hack: How to Take Charge of Your Brain and Program More Happiness Into Your Life, by Ellen Petry Leanse

(Full disclosure: Ellen is a very good friend of mine. But personal bias aside, this is an excellent book!)

Integrating concepts from spirituality and neuroscience, Ellen gives us very practical ideas on how to be happy. So if you’d like to have more time to do things you love, create real connections to the world around you, stop living your life on autopilot, reclaims focus for the things that matter, and reduce stress – this is the book for you.

Health warning: as we now know that happier people are more closely in touch with reality, this book could cause you to escape your bubble of belief and start seeing the world as it really is.

Are you ready to take the red pill?

Hi Roz – interesting books. Re: Happiness – browsing through my old journals I found the Geographical Journal of June 2015 has some very interesting papers on Happiness from Geographers – everything from sustainable, green funeral plots – to happiness of students’ locations. Royal Geographical Society library should have it if all else fails.

Thanks, Angela. I feel like I’ve got my happiness strategy pretty well figured out (after a lot of work!) but maybe we should see what we can do to enhance the happiness of the man in the White House, if it helps him to see reality more clearly?!